Creating Ibasho: Physical and social infrastructure that empowers elders and strengthens communities

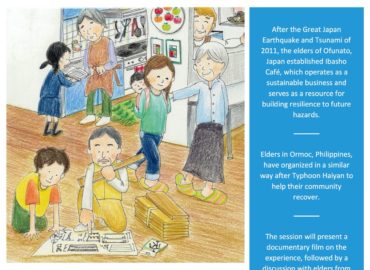

On June 20-21, 2018, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank hosted a symposium titled “Creating Ibasho: Physical and social infrastructure that empowers elders and strengthens communities.” The symposium’s aim was to build on knowledge gained by participants in a project called Ibasho, which empowers elders to become active and relevant members of their communities by developing and managing a physical infrastructure that becomes a community gathering place. Community elder leaders from the three pilot Ibasho sites (Japan, Nepal, and Philippines) discussed how they might better collaborate and shared their knowledge and experiences, both with each other and with technical expert and development partners. Participants explored topics such as effective community capacity building options, elder-led program planning strategies, and long-term sustainability in operations and management. They also discussed how elders could take a leadership role in strengthening community resilience and identifying next steps to better prepare for climate change and global aging.

Challenges of global aging

The work centered around some of the biggest public policy challenges of our aging society: the high cost of healthcare and elder care, the growing caregiver shortage, the social isolation of elders and their additional vulnerability during and after the natural disasters that are becoming more frequent and more destructive, thanks to climate change. Elders from all three countries have recently experienced catastrophic disasters caused by climate change. They discussed how they and other elders could help strengthen community resilience, making their communities better able to prepare for and survive both natural and man-made disasters. In addition to developing a sense of solidarity and shared vision amongst themselves, the elders talked to technical experts, economists, and representatives of NGOs, discussing those public policy issues and other challenges that may be solved if community members, local government, and policymakers can work together.

Preparing for the impact of aging in Asia: Overview

ADB Chief Economist Yasuyuki Sawada welcomed the participants and delivered opening remarks on trends and challenges related to aging in Asia. He emphasized the critical need of innovative ways to prepare for the societal changes that will result from a rapidly aging population, encouraging participants to continue empowering elders to build age-appropriate physical and social infrastructure that work for community members of all ages. He also suggested rethinking how we design and construct physical infrastructures, noting that they could better strengthen community ties if they integrate more civic engagement, thus heightening the community’s sense of ownership.

Disaster risk management and inclusive community resilience

World Bank Senior Social Development Specialist Margaret Arnold discussed the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR)’s disaster risk management efforts and how the work of elders through Ibasho connects with inclusive community resilience program that the World Bank has been implementing. She emphasized three lessons learned by the Ibasho participants:

- Everyone has to share the risk and responsibility in bridging the gap between local and national government.

- Communities need to be recognized as equal partners with expertise in building resilience.

- We must emphasize socially inclusive approaches to disaster risk management, since disasters discriminate: Poor people suffer more. If we don’t take care to include these people, she concluded, we miss out on expertise and insights they can bring to the table.

Emi Kiyota, founder of Ibasho, then briefly introduced the foundation and principles of Ibasho concept and how this concept has been implement in three three countries with support from the GFDRR in the World Bank Group.

Preparing for the impact of aging in Asia: workforce and long term care

ADB’s Aiko Kikkawa Takenaka, ERCI, spoke about issues raised by the aging workforce in Asia. She pointed out the importance of developing technologies to improve and maintain health and longevity, transform types of work and workplaces for older people, and help create a supportive labor market infrastructure.

ADB Technical Advisor for Social Development Wendy Walker shared demographical changes in Asia and discussed how Asian countries are adapting to this change, outlining health reform policies some countries have implemented. She observed that family and community care are the best vehicle for delivering the right level of elder care support, and that systems development and a strong emphasis on community-level actors are also needed.

Measuring the impact of Ibasho on health and social capital among elders

Takeshi Aida, Yasuyuki Sawada, and Yasuhiro Tanaka shared the initial results of the impact evaluation of the Ibasho project on health and social capital. The two main positive findings were that elders who participate in the Ibasho projects in Nepal and Philippines are in better health and have more friends in the community. Participants discussed the importance of hard data to mobilize various stakeholders, especially policymakers. The impact evaluation revealed the challenges of community-based research design, such as maintaining the integrity and accuracy of the data and cross-cultural and generational translation of the survey contents and outcome.

Role of elders in the recovery process

Throughout the workshop, elders from the three countries were asked to think critically about the obstacles to implementation and self-sustainable operation in their communities. In particular, the discussion focused on two topics 1) community capacity building, and 2) long term self-sustainable operation through livelihood projects, such as farming, farmer’s market, or jewelry making. They also discussed the steps elders can take to maintain Ibasho principles when projects scale up. Below are some comments from the community members.

“As elders and women, we should do something for the community and not just sit down and watch. We are empowered after meeting people from Philippines and Japan. We learned best practices that we can bring back to Nepal and implement.” (participant from Nepal)

“The typhoon was a sad and emotional memory but also showed the resilience and contribution of the elders in the community. We have to continue and move forward. We are grateful to the World Bank and Ibasho for helping us to not get left behind, transforming elders to become productive members of the society. Respect toward elders, especially from the younger generations in the Philippines, is fading. Through Ibasho, we are able to be a role model for them and be useful members of the society through Ibasho projects like the recycling of plastics.” (Participant from the Philippines)

“We are thankful to the World Bank, ADB, and Ibasho for bringing people together towards a common purpose and happy that we are able to meet other elders in The Philippines and Nepal. It was difficult to rise up and recover our life again. We lost properties, friends, family members. Ibasho played a huge part in helping them stand again and live a normal life.” (Participant from Japan)

Learning from Ibasho coordinators

Ibasho coordinators shared their experience working with elders. “It is very impressive that elders are actively volunteering for this and to see the elderly lead a community. Natural disaster caused hardships to many. However, it also created opportunities for people from different parts of world to form friendship and solidarity,” said Ian Parrucho, an Ibasho Philippines local coordinator.

Santoshi Rana, a local coordinator in Nepal, said: “Working closely with elders taught me why Ibasho is truly needed in our communities. The beauty of Ibasho is that disaster may have brought us together but it also unleashes our potential and built the community that we are now.”

The coordinators also shared some concerns and challenges that they have explained through working with the elders to develop and implement Ibasho projects locally. For instance, the Ibasho model and governance is flexible, adapting as needed to the circumstances. In the Philippines, it must be tailored fit to each situation, as no model can be applicable in all barangay. They also agreed that it was challenging at times for elders to adjust to taking the lead and for “experts” to adjust to taking a back seat, as Ibasho facilitates rather than deciding what elders can or should do. However, that is an important part of Ibasho’s philosophy, and community elders must always lead the process.

Lessons learned from the Symposium

1. Ibasho implementation

- Use existing community organizations to identify champions for Ibasho activities when starting the program.

- Establish shared expectations and work plans with local elders in the early stages of development

- Adjust program development and planning according to local and cultural events—and, most importantly, at a pace that is comfortable for the elders.

1-1. Capacity building

- Educate both the elders and the local coordinator to shift their mindset from the traditional dependency model to the interdependency approach that is a core part of Ibasho’s eight principles.

- Plan and deliver many small wins with elders; concrete community upgrading projects that allow community members to see the contribution elders are making.

- Expose elders to a variety of possible livelihood projects they can choose from and integrate into their group effort.

- Find ways to generate income, so the group effort can grow and be sustained for a long period of time.

- Reach out and educate the family members about the Ibasho project, so they will be supportive of their loved ones to help community members through the Ibasho activities.

- Integrate development of business and financial plans to make the project sustainable among the community member over the long term.

1-2. Design and construction

- Plan carefully to ensure that the purpose, accessibility, and the scale of the physical infrastructure fit the needs and capacity of the elders.

- Understand the cultural significance of the place where the Ibasho hub is installed in order to maintain the integrity of the place and community.

- Consider improving or renovating an already existing place as the Ibasho hub rather than building from scratch, to save time and money and facilitate integration into the community.

- Discuss with community elders about to what extent they can manage the construction or renovation.

1-3. Local coordinators

- Establish clear lines of communication between Ibasho and the local office

- Set up and manage expectations from community members in the early stages

- Consistently communicate Ibasho’s eight principles to community members from the start.

2. Research

Methodologies

- Reconsider the length and content of survey questions to make it easier for community members to collect data.

- Develop a database where all the data from new projects can be stored.

Results

- Develop outcomes that help local elders improve their programs.

- Develop outcomes that help other communities learn from each other.

- Disseminate the outcomes to all Ibasho community members so they can learn from them.

3. Peer-to-peer knowledge exchange

- Directly learning from the elders about successes and challenges in implementing and maintaining the Ibasho program is an excellent way to motivate and improve current projects.

- Establish continuous peer-to-peer support among the elders from different locations

- Establish continuous collaboration for figuring out how to make the operation self-sustaining.

- Capture and record the knowledge gained in these experiences. It is very helpful for elders to learn that the challenges and difficulties faced in each country are similar, and to share knowledge about how to overcome them.

4. Working with local government

- Gaining consistent help from the local government is challenging.

- Much of the information needed was not available online or at City Hall.

- Changes of regulations usually were not publicized, contributing to the large amount of time and energy needed to fulfill the required paperwork and inspections for Ibasho’s activities.

- The cost of establishing a local organization was too high for local elders to be able to establish their own entity without outside help.

- Much of the required paperwork was complex, so elders needed to hire an accountant and/or lawyer to prepare them. That extra effort and expense makes it more difficult to develop grassroots program like Ibasho to allow elders to contribute to their communities.

Conclusion

During their two-day peer-to-peer knowledge exchange, elders gained a deeper understanding of the role of Ibasho and formed meaningful relationships with other elders. A Japanese elder said, “This event inspired and empowered me to do something when going back to Japan.” A Nepali elder said he found it useful to learn more about the Ibasho locations in the Philippines and Japan. “Mainly the learning would be on how to deal with situations all of us have had to deal with. We have a deeper understanding on how Ibasho operates in different Ibasho communities, and that helped us come up with new ideas on how to improve our work.” An elder from the Philippines impressed by the strong intergenerational effort shared: “We learned from Nepal to serve other groups, like women, to create more interest in joining Ibasho Philippines.”

The symposium was a great success, bringing together elder leaders with economists, technical experts, and NGO representatives. Although the younger “experts” have traditionally been considered to have all the answers, they realize that their solutions to the great challenges of global aging and climate change stand little chance of success without effective collaboration with local communities, which includes empowering elders as change agents. The participants left with a renewed conviction of the strength of elders, the importance of their role in their communities, and the need for a coalition of external supports to help them take a leadership role and help make their communities stronger and more resilient. The conversation they started across countries and generations will inspire more elder-led initiatives in the future.

This activity was made possible with the financial support from GFDRR through the Inclusive Community Resilience program and the Japan – World Bank Program on Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Management in Developing Countries program, and technical support from the Disaster Risk Management Hub Tokyo.